MYTH 1: ROMANS WERE ALL ITALIANS

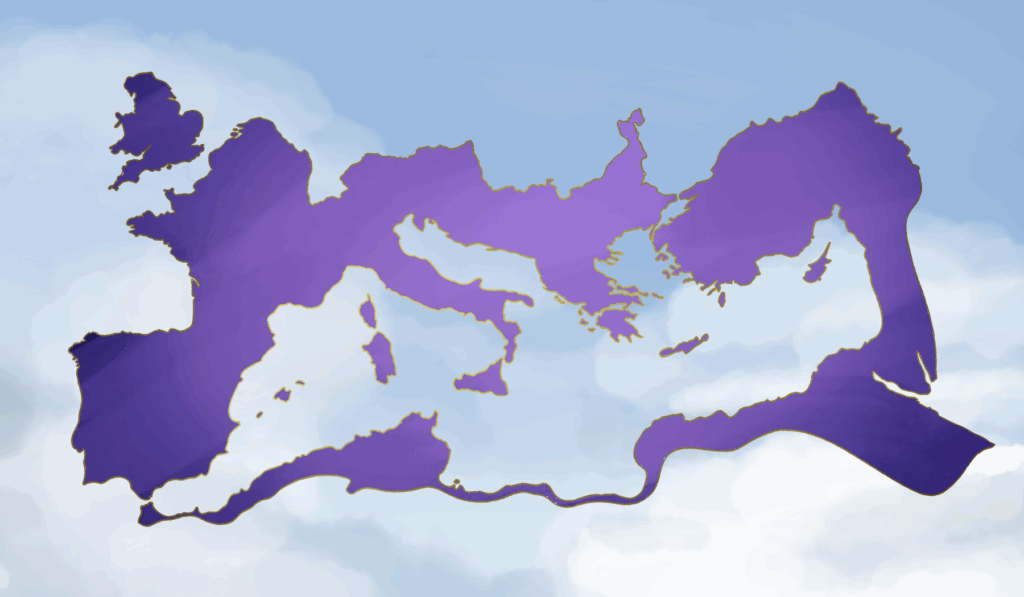

Out of all the myths, this one pisses me off the most. Ask the average person to picture a Roman, and they’ll probably imagine a bunch of dark-haired olive-skinned Italians in togas, yelling “Et tu, Brute?” in thick accents. That stereotype has stuck around and it doesn’t help that the modern state of Italy has long promoted the idea that it’s the direct heir to Roman greatness, as if only Italians can truly claim the Roman legacy. But this view is shaped by our modern concept of the nation-state, which didn’t exist in the ancient world. Sure, Rome began in what we now call Italy, but the meaning of “Roman” changed radically over time. In the early days, being Roman meant being from the city of Rome and its surrounding Latin communities. It was a narrow, local identity tied to central Italy and the Latin language. But as Rome expanded and absorbed new peoples, “Roman” evolved from an ethnic label into a civic one. It became less about where you were born and more about how you lived. Whether you followed Roman law, served in the army, paid taxes, and participated in Roman institutions.

By the start of the Empire, Rome had the whole Mediterranean region and already there were tons of people who were considered Roman that had no Italian ancestry. Then in 212 AD Caracalla’s Edict, which granted citizenship to basically every free man in the empire, meant that anyone could be Roman. Spaniards, Gauls, Syrians, Egyptians, Berbers. Any remaining notion of an Ethnic Roman identity was entirely done away with and it was now completely a civic one. And indeed, some of the most famous Romans weren’t even Italian. Trajan and Hadrian were from Hispania. Septimius Severus was of Berber descent from North Africa. Constantine the Great was of Illyrian descent. Galen, the famous doctor, was Greek. Plotinus, the philosopher, was also Greek. The face of Rome was incredibly diverse. By the Middle Ages, most people who called themselves “Romans” weren’t Italian at all, they were mostly Greek-speaking citizens of the Eastern Roman Empire, which we now call the Byzantine Empire. That wasn’t some offshoot, it was Rome, still alive and well centuries after the fall of the Western half. To give a modern day example, think of it like the word “American.” At first, it mostly referred to Anglo settlers, but as America grew and waves of immigrants came in, being American became less about ethnicity and more about belonging to a system, a shared culture, law, and identity. The same happened with Rome. Being Roman was no longer about blood, but about belonging to a system, a culture, and a legacy that transcended borders and backgrounds.

MYTH 2: THE ROMAN EMPIRE WAS A MONARCHY

This one’s easy to assume, after all, they had emperors, right? A guy at the top with all the power, giving orders, living in a palace, wearing purple. Sounds like a king. But that’s like seeing armored dudes swinging swords and assuming its the Medieval Era. The truth is way more complicated. The Roman Empire wasn’t a monarchy in the traditional sense. In fact, the Romans hated kings. Their entire identity was built around not being ruled by one. The Roman Republic had overthrown its last king centuries earlier, and the word rex (king) was like a curse word. To call someone a king was basically an insult, it meant tyranny, oppression, betrayal of the Republic. So when Augustus rose to power, he played it smart. He didn’t call himself a king. He called himself princeps “first citizen.” The Senate still met, consuls were still elected, and laws still technically went through the motions. On paper, the Republic was alive. But in reality? Augustus had all the real power, control of the army, the treasury, and the ability to overrule anything or anyone. What existed was essentially a military dictatorship, dressed up as a continuation of republican tradition. This setup known as the Principate let emperors rule with near-total authority while keeping up the illusion of shared governance. The Senate nodded along, but everyone knew who was really in charge.

Eventually, though, the mask slipped. During the Crisis of the Third Century, everything fell apart. Civil wars, plagues, constant invasions, and emperors rising and falling every few years. Power now came straight from the sword. If the army backed you, you were emperor. If they didn’t, you were dead. Emperor Diocletian was the one who made this “mask off” approach official. He ruled as a true autocrat. No more pretending to be a humble citizen. Now the emperor was expected to be treated like a divine figure who openly had power over the military and bureaucracy. The Senate? It became a rubber stamp. Imperial power was now blunt, formalized, and openly based on military might. So was the Roman Empire a monarchy? Not in the way most people think. Compared to medieval Europe, where succession was usually hereditary and monarchs could be old, women, or even incompetent who often died rather peacefully, Rome didn’t follow that script. Power didn’t pass down peacefully through bloodlines. It passed through violence. Most Roman emperors were young, military-aged men who seized power through force, not birthright, and many of them died violently too. You didn’t inherit the purple, you fought for it.

MYTH 3: CHRISTIANITY WAS INEVITABLE

This myth is really frustrating but also understandable, given how Christianity is the world’s largest religion and has been the West’s one and only religion for over 1,500 years. It’s easy to look back and assume Christianity’s rise was inevitable, like it was always destined to take over. I’ve heard people claim that Christianity was 10-25% of the population by the turn of the 4th century AD and it was rapidly spreading because, “People became Christian because the Roman afterlife sucked,” or “Christianity grew because Christians were charitable while pagans were cold and cruel,” or even “Christianity won because pagans killed babies and Christians adopted them.” And I’ve heard all these from people who weren’t Christian at all. But here’s the shocker, at the time of Emperor Constantine’s conversion in the early 4th century AD, Christians made up only about 1% to 2% of the entire Roman Empire’s population and were mostly concentrated in a handful of Eastern cities. The average Roman in this era would have been a rural farmer that probably didn’t even know about Christianity. Constantine’s decision to convert wasn’t as revolutionary as we might think. Roman emperors were often apart of strange eccentric religious movements and his conversion was likely a sincere personal choice, but it was also likely a political move considering how centralized Christianity was even before Imperial support. Most importantly, Constantine’s successors continued to support Christianity, gradually turning it into the favored religion of the state.

This process wasn’t peaceful or universally accepted, though. Paganism (which is really any religion not Christian rather than a single specific religion) was still strong and dominant in much of the Empire during the 4th century AD. There was even an emperor called Julian the Apostate who left the Christian religion and tried to reverse the Christianization of the empire by promoting a pagan revival. Unfortunately for him, his reign was short and he died before he could implement his plans, and no one followed in his footsteps to revive the Ancient Religions of the Empire on an imperial scale. The turning point came in 380 AD when Emperor Theodosius I declared Nicene Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire. This decree ushered in an era of harsh state backed-persecution against pagans and heretical Christian groups alike. Pagan temples were looted or destroyed by mobs, traditional festivals were banned, and even the Vestal Virgins, guardians of Rome’s thousand-year-old sacred fire, were disbanded. Yet despite this intense pressure, pagan beliefs and practices still remained strong. They endured quietly both in intellectual circles and among common people, even as subsequent rulers like Justinian I intensified persecution. Intellectual centers of pagan philosophy, such as the famous Platonic Academy in Athens, were shut down in 529 AD, and laws were passed to coerce pagans into converting to Christianity. By 600 AD any strongholds of the Old Faiths in the Mediterranean had been wiped out. So no, Christianity was by no means inevitable. Its rise to dominance was largely due to the constant patronage of Roman emperors and the brutal suppression of other faiths. Had Constantine never converted or even if Julian the Apostate had a longer reign and carried out his plans, it’s very much possible Christianity would have remained a small regional religion rather than humankind’s most influential religion.

MYTH 4: THE ROMAN EMPIRE WAS SUPER ADVANCED

When we look at the Roman Empire, it’s tempting to see them as a civilization bursting with progress and innovation. After all, they built massive aqueducts that carried water across miles of terrain, an expansive road network that stretched over 50,000 miles, cities that had over a million people, and colossal public monuments like the Colosseum and the Pantheon. They had complex legal systems, professional standardized armies, and concrete. Surely, this was a society centuries ahead of its time… right? But while Rome was impressive in many ways, calling it “super advanced” overlooks a critical truth, the Roman world wasn’t a culture of innovation. It was a culture of preservation. The Romans didn’t think about time or history the way we do. To them, history moved in cycles, not forward. Their ideal wasn’t to reshape the future but to recapture the past, especially a mythical, idealized past they associated with the founding of Rome and the heroic age of their ancestors. This meant Romans weren’t driven by the idea of progress. They valued tradition, order, and stability over experimentation or change. Their intellectual culture, especially in philosophy and politics, leaned heavily on inherited Greek ideas. Most Roman scholars weren’t trying to question old authorities, they were trying to transmit them. The greatest thinkers of Rome, like Pliny the Elder, Seneca, or Galen, didn’t think of themselves as scientists. In fact, science as a structured discipline didn’t even exist. They worked within inherited frameworks, relying on texts, received wisdom, and anecdotal experience rather than the scientific method as we understand it today (observation, experimentation, and falsifiable hypotheses). Engineering and architecture were feats of practical mastery and trial and error, but rarely supported by broader theoretical understanding. In fact, if you took a Roman from 1 AD and dropped him into the Roman Empire of 301 AD, from a technological standpoint he wouldn’t really see any difference. In fact he would probably feel more at home than someone from 1945 AD would in 2025 AD. Roads, buildings, tools, even surgery and education, most of it would be strikingly familiar. Despite the passage of three centuries, not much had changed in terms of technology.

The empire’s bureaucracy and infrastructure were brilliant at maintaining and replicating what already existed, but they weren’t designed to foster novelty. Innovation, when it did happen, often came from necessity or from the fringes, not from a cultural desire to improve. Even technological inventions like Hero of Alexandria’s steam engine were treated as novelties or curiosities, not as practical machines to be scaled or improved. His ideas sat on a shelf for centuries because the economy, worldview, and culture of Rome didn’t prioritize transformation. So yes, the Roman Empire was “advanced” in the sense that it was organized, resilient, and capable of astonishing feats of construction and administration. But it was not forward-looking. It didn’t have an industrial mindset, nor a scientific revolution waiting in the wings. It had no culture of open experimentation or innovation like that which would eventually blossom in Early Modern Europe. In this way, Rome was not the forerunner of modern progress as we often imagine it, it was a custodian of the past. And when we judge it by that standard, we see a different picture. Not a civilization surging ahead, but one dedicated to keeping the old world standing as long as it possibly could.

MYTH 5: ROME FELL IN 476 AD

We’ve all heard the story. Rome, the shining light of civilization, was on its last legs in the 5th century AD. And then in 476 AD, after facing endless hordes of barbarians, the Western Roman Empire fell, starting what is called kicking THE DARK AGES. But of course the reality is much messier. Rome was already a shell of its former self in the 5th century AD. Ruined cities, low literacy, and constant violence. What actually happened in 476 AD is that the last Western Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer. This event marked a major political shift, but it definitely wasn’t a shocker to anyone in Europe at the time. After all Roman authority basically collapsed in the West decades ago. Roman culture and identity very much continued even after the political system behind it was no more. In fact, Roman institutions, laws, and culture persisted for centuries after 476 AD, especially among the aristocracy and in the surviving cities. Many of the so called “barbarian” rulers who took over the former Western Empire didn’t see themselves as destroyers of Rome, rather, they styled themselves as Roman kings or continued to use Roman titles, legal systems, and administrative practices to legitimize their rule. They still event hosted games in the old arenas. Far from erasing Roman culture, these new powers often embraced it as a source of authority and stability and was used to rebuild after the decline of the Late Roman World.

The Catholic Church played an essential role in preserving Roman traditions, too. As the political power of Rome waned and institutions collapsed, the Church saw itself as Rome’s spiritual successor and became the main guardian of Roman law, the Latin language, education, and cultural memory. Bishops and clerics maintained the administrative framework and legal codes that shaped medieval Europe. Cities like Rome, Ravenna, Milan, and others remained vibrant centers of Roman governance and culture well into the Early Middle Ages. This enduring Roman identity also explains why Emperor Justinian’s military campaigns in the 6th century AD didn’t view it as a conquest but a restoration. Justinian viewed his attempts to restore Roman control and prestige over what he saw as usurped territories. It’s also why Charlemagne’s coronation as Emperor in 800 AD was such a landmark event. It wasn’t just about crowning a powerful Frankish king, but about reviving the legacy of Rome in Western Europe and asserting continuity with the former empire. Over many centuries however, with no unified state in the West, languages diverging, and the mixing of Roman, Germanic, and Christian elements does more regional and new identities start to emerge. So, Rome didn’t simply fall in 476 AD. Instead, its identity continued living on in the West, far beyond the deposition of an emperor. What emerged from the ashes of the Western Roman Empire wasn’t an end, but an evolution, as its politics, religion, and identity laid the foundations for what we now call Western Civilization.

Like the subject of Ancient Rome? You may enjoy this artwork here I made where I discuss the connection between Roman Emperors and Christianity.

REFERENCES

Myth 1: Greg Woolf, Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul

Myth 2: Richard Alston, Rome’s Revolution: Death of the Republic and Birth of the Empire

Myth 3: Peter Heather, Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, AD 300-1300

Myth 4: David C. Lindberg, The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450

Myth 5: Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians